My thanks to Graham for recommending this book!

Cryptonomicon is effectively four stories in one book, although the stories are closely linked, as you might imagine. As it is hard to look in-depth at any particular subject in a book of this length, I will mainly show one of the excellences of Stephenson's style, which is his ability to write distinctly when narrating for each of the main protagonists. In this regard Stephenson outdoes Terry Pratchett (himself no slouch when it comes to style), whose writing I find Stephenson's most resembles, for Pratchett tends toward stylistic uniformity, although unlike some of the other authors whose books I have written commentaries for here on The Marginal Virtues, Pratchett's singular style is excellent.

But back to Cryptonomicon. The edition I am using for this commentary was published in 1999 by Avon Books (an imprint of HarperCollins). It is impossible for me to treat the book's plot with the kind of consideration it deserves, so I will generally try to choose passages which are representative of the distinct styles in which Stephenson writes with respect to the protagonists, but which are not necessarily crucial to the movement of the plot. If time and space permit, I would also like to briefly compare Cryptonomicon to, of all things, The Lord of the Rings. Such a comparison is not inapt; indeed, one of the protagonists, Randy Waterhouse, occasionally interprets what is going on around him in Tolkienian imagery, and there is one passage (which I hope to quote at length) which displays a striking coherence to an idea much more briefly elucidated in Tolkien's work. I won't go into any more detail here, nor do I promise that such a comparison will, in fact, take place. If you like, it's something for you to think about, should you get your hands on a copy of Cryptonomicon.

Finally, Cryptonomicon is true to life, and about two-thirds of it, on the whole, is set during the Second World War. I have included the labels 'profanity' and 'sex' because there is a fair amount of swearing, and not only sex, but also moments where characters are thinking about sex (or about people with whom they would like to have sex) and have, shall we say, appropriate physiological reactions to these thoughts. Actually, the distinction between Stephenson's various 'narrative dialects' (you might call them) is nowhere more evident than in the various sexual encounters in which three of the four protagonists engage. All that said, Cryptonomicon is not a smutty book, simply realistic, in that people in the book swear (some more than others), and either have or think about having sex with other people. In terms of what I will be citing, I won't be quoting anything from sex scenes (unless it is suitably suggestive, rather than explicit), but I won't be able to help quoting profane utterances, as there are, after all, quite a few of those in Cryptonomicon. You have been warned.

Well, enough of all that rigomarole. Let's get on with Cryptonomicon.

There are three storylines which dominate the first two-thirds of Cryptonomicon, and fourth which begins (if memory serves) more or less halfway through but which becomes of greater importance as the plot moves forward. Three of these are set during the Second World War.

The 'modern-day' storyline (set, more or less, in the late nineties) follows Randy Waterhouse, an entrepreneur and computer expert looking for riches and love in the Philippines.

The first of the WWII storylines follows Randy's grandfather, Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse (as he is almost invariably introduced), an eccentric mathematical genius who becomes involved in the highest levels of Allied cryptanalysis.

The second follows Bobby Shaftoe, a Marine, who ends up travelling all over the world when he becomes enmeshed, at a lower level, in the intrigues in which Lawrence Waterhouse is involved.

The third, latecoming, storyline is that of Goto Dengo (whose name we would render in our fashion as Dengo Goto), a Japanese soldier and miner who is ordered to build an underground facility for a mysterious purpose in the Philippines.

Incidentally, Stephenson throughout Cryptonomicon use the adjectival form 'Nipponese' (and 'Nippon' for the name of the Home Islands), instead of 'Japanese'. I understand that in the Japanese language, 'Nippon' is the name of the land, but this linguistic exactitude does not, I should think, extend to the adjectival form (which would not be found in Japanese). It makes a certain amount of sense in the WWII storylines (or at least in the English-speaking ones), where the characters occasionally - who am I kidding; frequently - and derogatorily refer to the Japanese as 'Nips', but I am otherwise at a loss to grasp why Stephenson adopts this form, rather than using the conventional 'Japanese' or 'Japan'. He does use the usual forms, either when they are part of the name of a product (e.g., Randy once is served 'Japanese Snack' on an airflight), or when a character uses them in speech. But the question again arises, why 'Nipponese' rather than 'Japanese'?

Anyway, let's compare the styles. A great place from which to start is, in fact, the distinct styles in which Stephenson describes the sexual encounters of three of his four protagonists, as I noted above. I won't go into explicit detail, however (Stephenson himself is not especially explicit, for what it is worth).

In December 1941, Marine Bobby Shaftoe is stationed in Manila, where, predictably, he has met and fallen in love with a local girl by the name of Glory (an Anglicisation, I presume, of 'Gloria'), whose family is of some prominence. Unsurprisingly, they arrange a tryst:

Bobby Shaftoe is not one to lose his cool in the heat of action, but the rest of the evening is a blurry fever dream to him. Only a few impressions penetrate the haze: alighting from the taxi in front of a waterfront hotel; all of the other boys gaping at Glory; Bobby Shaftoe glaring at them, threatening to teach them some manners. Slow dancing with Glory in the ballroom, Glory's silk-clad thigh gradually slipping between his legs, her firm body pressing harder and harder against his. Strolling along the seawall, hand in hand beneath the starlight. Noticing that the tide is out. Exchanging a look. Carrying her down from the seawall to the thin strip of rocky beach beneath it.We turn to another of Stephenson's styles in Cryptonomicon. Lawrence Waterhouse is an eccentric genius, and begins the novel as incredibly inept in many ways, but by the end of it is a clever and canny man. One of his most notable exploits is his successful wooing of a young woman named Mary while assigned to Australia as part of his work in Department 2702, a top-secret Allied effort to keep the Axis powers unaware of the fact that their codes have been broken. After a disastrous attempt to flirt with Mary at a dance, Lawrence has a sudden burst of inspiration early one Sunday morning:

By the time he is actually fucking her, he has more or less lost consciousness, he is off in some fantastic, libidinal dream. He and Glory fuck without the slightest hesitation, without any doubts, without any troublesome thinking whatsoever. Their bodies have spontaneously merged, like a pair of drops running together on a windowpane. If he is thinking anything at all, it is that his entire life has culminated in this moment. His upbringing in Oconomowoc, high school prom night, deer hunting in the Upper Peninsula, Parris Island boot camp, all of the brawls and struggles in China, his duel with Sergeant Frick, they are wood behind the point of a spear. [pp. 58-9] I can only presume that Stephenson's image at the end of the passage is a pun, and that fully intended. The image of bodies merging in lovemaking like drops (of water, it should have read) running together on a windowpane is quite good. In any case, Stephenson's 'Shaftoe style' is evinced here by short, sharp sentences. They are to-the-point, although, oddly, in this instance many of them are indirect: 'noticing', 'exchanging', 'alighting' (a good choice of verb if there ever was one), and so on. The terseness extends to all of Bobby Shaftoe's activities; in love, as we have seen, and, as we shall see, in war.

The alarm clock. Rod [Lawrence's roommate in the boarding house in which he is living in Brisbane] rolls out of bed like it's a Nip air raid. ...Waterhouse is late for a meeting with his superior, Earl Comstock:

[Lawrence] rolls out of bed, startling Rod, who (being some sort of jungle commando) is easily startled. "I'm going to fuck your cousin until the bed collapses into a pile of splinters," Waterhouse says.

Actually, what he says is, "I'm going to church with you." But Waterhouse, the cryptologist, is engaging in a bit of secret code work here. He is using a newly invented code, which only he knows. It would be very dangerous if the code is ever broken, but this is impossible since there is only one copy, and it's in Waterhouse's head. Turing [mathematician Alan Turing] might be smart enough to break the code anyway, but he's in England, and he's on Waterhouse's side, so he'd never tell. [p. 712] Honestly, everything is about codes with Waterhouse. To make a long story short (for this episode continues for quite a few pages), Waterhouse successfully woos Mary. Mainly I quoted this passage because the incongruity between Lawrence Waterhouse's words, 'I'm going to church with you,' and their intended meaning, is so funny (or at least, I found it funny).

[Comstock] checks his watch. They are running five minutes behind schedule. He looks out the window and sees that his jeep has returned; Waterhouse must be in the building. "Where is the extraction team?" he demands.Finally, Randy Waterhouse, grandson of Lawrence, is able to consummate his growing romance with Amy Shaftoe, granddaughter of Marine Bobby Shaftoe, while waiting in a jeep to drive to a hidden location in the Philippines:

Sergeant Graves is there a few moments later. "Sir, we went to the church as directed, and located him, and, uh—" He coughs against the back of his hand.

"And what?"

"And who is more like it, sir," says Sergeant Graves, sotto voce. "He's in the lavatory right now, cleaning up, if you know what I mean." He winks.

"Ohhhh," says Earl Comstock, cottoning on to it.

"After all," Sergeant Graves says, "you can't blow out the nasty pipes of your organ unless you have a nice little assistant to get the job properly done."

Comstock tenses. "Sergeant Graves—it is critically important for me to know—did the job get properly done?" [italics original]

Graves furrows his brow, as if pained by the very question. "Oh, by all means sir. We wouldn't dream of interrupting such an operation. That's why we were late—begging your pardon."

"Don't mention it," Comstock says, slapping Graves heartily on the shoulder. "That is why I try to give my men broad discretion. It has been my opinion for quite some time that Waterhouse is badly in need of relaxation. He concentrates a little too hard on his work. [...] And I think you have made a pivotal, Sergeant Graves, a pivotal contribution to today's meeting by having the good sense to stand off long enough for Waterhouse's affairs to be set in order." [pp. 735-6] One of the characteristics of Stephenson's 'Waterhouse style' is a suffused sense of humour. We shall see other passages characteristic of the 'Waterhouse style' which provide other stylistic notes, but this undercurrent of laughter is a constant. There is a sense in which everything Lawrence Waterhouse does is somehow amusing, whether it is getting help from the love of his life with an, ahem, delicate operation, or rambling off on some mathematical point, and so on.

[Amy] ends up on Randy's lap, lying sideways on top of him, her head on his chest. "Close the door," Amy says, and Randy does. The she squirms around until she's face to face with him, her pelvic center of gravity grinding mercilessly against the huge generalized region between navel and thigh that has, in recent months, become one big sex organ for him. She brackets his neck between her forearms and grabs the carotid supports of the whiplash arrestor. He's busted. The obvious thing now would be a kiss, and she feints in that direction, but then reconsiders, as it seems like some serious looking is in order at this time. So they look at each other for probably a good minute. It's not a moony kind of look that they share, not a starry-eyed thing by any means, more like a what the fuck have we gotten ourselves into thing. As if it's really important to both of them that they mutually appreciate how serious everything is. Emotionally, yes, but also from a legal and, for lack of a better term, military standpoint. But once Amy is satisfied that her boy does indeed get it, on all of these fronts, she permits herself a vaguely incredulous-looking sneer that blossoms into a real grin, and then a chuckle that in a less heavily armed woman might be characterized as a giggle, and then, just to shut herself up, she pulls hard on the stainless steel goalposts of the whiplash arrestor and nuzzles her face up to Randy's and, after ten heartbeats of exploratory sniffling and nuzzling, kisses him. It's a chaste kiss that takes a long time to open up, which is totally consistent with Amy's cautious, sardonic approach to everything, as well as with the hypothesis, alluded to once while they were driving to Whitman, that she is in fact a virgin.Stephenson's 'Waterhouse style' is probably the most noticeably distinct. Its distinction is made clear in two ways, at least so far as I have been able to tell. The first is that only when writing about Lawrence Waterhouse does Stephenson digress, you might say, into a mathematical or cryptological musing of the sort Lawrence would be doing under the circumstances (as we shall see). The second is that Lawrence at first does not really perceive the world as we would, and Stephenson writes about his adventures in such a way to make that plain. As I said, he becomes craftier and (for want of a better word) worldlier as Cryptonomicon progresses, and so the second means by which the 'Waterhouse style' is made distinctive gradually recedes. But let us take a closer look.

Randy's life is essentially complete at the moment. He has come to understand during all of this that the light shining in through the windows is the light of dawn, and he tries to fight back the thought that it's a good day to die because it's clear to him that although he might go on from this point to make a lot of money, become famous, or whatever, nothing's ever going to top this. Amy knows it too, and she makes the kiss last for a very long time before finally breaking away with a little gasp for air, and bowing her head so that her brow is supported on Randy's breastbone, the curve of her head following that of her throat, like the coastline of South America and Africa. [italics original; pp. 1079-80] There's more to their lovemaking than this, of course, but since this scene is the, ah-ha, climax of Randy's and Amy's relationship thus far in Cryptonomicon, Stephenson lavishes it with explicit detail, although when you read it it displays a certain tenderness. There is also a geeky reference to Star Wars, but it has to be read in context for full effect. In any event, I will quote from the scene no further. This sexual encounter between Randy and Amy has somewhat of the same significance as that between Bobby Shaftoe and Glory, which I quoted above (the which resulted in the conception of the child who would become Amy's father, incidentally), but the differences between them are already noticeable, and are even more telling if you include the two paragraphs of Randy and Amy actually going at it. Stephenson is much more descriptive, for one. There is a reference to a famous science fiction film, for another (references to nerdy stuff are characteristic of Stephenson's 'Randy style'); in no other storyline do the characters compare their situations to books or films the way Randy Waterhouse does. Finally, although Stephenson writes with a unified style, we can see that his 'Shaftoe style' is, in a word, pugnacious; his 'Waterhouse style' ironic; and his 'Randy style' relaxed and fluid. (The style he crafts for Goto Dengo might be called tragic, since that is the tenor of those passages; we shall see this for ourselves.)

First, we'll look at a passage exemplifying the second distinguishing feature of the 'Waterhouse style', the bombing of Pearl Harbour on the seventh of December, 1941:

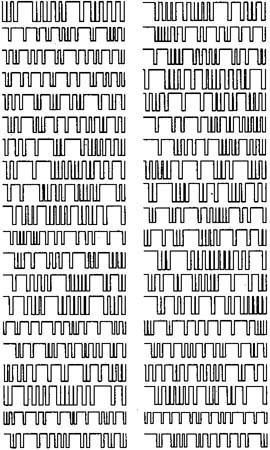

Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse and the rest of the band are up on the deck of the Nevada one morning, playing the national anthem and watching the Stars and Stripes ratchet up the mast, when they are startled to find themselves in the midst of one hundred and ninety airplanes of unfamiliar design. Some of them are down low, traveling horizontally, and others are up high, plunging nearly straight down. The latter are going so fast that they appear to be falling apart; little bits are dropping off of them. It is terrible to see—some training exercise gone miserably awry. But they pull out of their suicidal trajectories in plenty of time. The bits that have fallen off them plunge smoothly and purposefully, not tumbling and fluttering as chunks of debris would. They are coming down all over the place. Perversely, they all seem to be headed for the berthed ships. It is incredibly dangerous—they might hit someone! Lawrence is outraged.Since my quotation and discussion of the second aspect of the 'Waterhouse style' which Stephenson deploys to create a distinctive manner for Lawrence Waterhouse was quite long, I will limit my look at the first aspect of the style to an abridged quotation. Just to remind us of what the first aspect of the 'Waterhouse style' is, it is frequent mathematical or cryptological digression. This quotation includes inset diagrams (original to Cryptonomicon), which I have embedded courtesy of e-reading.org.ua and euskalnet.net.

There is a short-lived phenomenon taking place in one of the ships down the line. Lawrence turns to look at it. This is the first real explosion he's ever seen and so it takes him a long time to recognize it as such. He can play the very hardest glockenspiel parts with his eyes closed, and The Star Spangled Banner is much easier to ding than to sing.

His scanning eyes fasten, not on the source of the explosion, but on a couple of airplanes that are headed right toward them, skimming just above the water. Each drops a long skinny egg and then their tailplanes visibly move and they angle upwards and pass overhead. The rising sun shines directly through the glass of their canopies. Lawrence is able to look into the eyes of the pilot of one of the planes. He notes that it appears to be some sort of Asian gentleman.

This is an incredibly realistic training exercise—down to the point of using ethnically correct pilots, and detonating fake explosives on the ships. Lawrence heartily approves. Things have just been too lax around this place.

A tremendous shock comes up through the deck of the ship, making his feet and legs feel as if he had just jumped off a ten-foot precipice onto solid concrete. But he's just standing there flatfooted. It makes no sense at all.

The band has finished playing the national anthem and is looking about at the spectacle. Sirens and horns are speaking up all over the place, from the Nevada, from the Arizona in the next berth, from buildings onshore. Lawrence doesn't see any antiaircraft fire going up, doesn't see any familiar planes in the air. The explosions just keep coming. Lawrence wanders over to the rail and stares across a few yards of open water towards the Arizona.

Another one of those plunging airplanes drops a projectile that shoots straight down onto Arizona's deck but then, strangely, vanishes. Lawrence blinks and sees that it has left a neat bomb-shaped hole in the deck, just like a panicky Warner Brothers cartoon character passing at high speed through a planar structure such as a wall or ceiling. Fire jets from that hole for about a microsecond before the whole deck bulges up, disintegrating, and turns into a burgeoning globe of fire and blackness. Waterhouse is vaguely aware of a lot of stuff coming at him really fast. It is so big that he feels more like he is falling into it. He freezes up. It goes by him, over him, and through him. A terrible noise pierces his skull, a chord randomly struck, discordant but not without some kind of deranged harmony. Musical qualities aside, it is so goddamned loud that it almost kills him. He claps his hands over his ears.

Still the noise is there, like red-hot knitting needles through the eardrums. Hell's bells. He spins away from it, but it follows him. He has this big thick strap around his neck, sewn together at groin level where it supports a cup. Thrust into the cup is the central support of his glockenspiel, which stands in front of him like a lyre-shaped breastplate, huge fluffy tassels dangling gaily from the upper corners. Oddly, one of the tassels is burning. That isn't the only thing now wrong with the glockenspiel, but he can't quite make it out because his vision keeps getting obscured by something that must be wiped away every few moments. All he knows is that the glockenspiel has eaten a huge quantum of pure energy and been kicked up to some incredibly high state never before achieved by such an instrument; it is a burning, glowing, shrieking, ringing, radiating monster, a comet, an archangel, a tree of flaming magnesium, strapped to his body, standing on his groin. The energy is transmitted down its humming, buzzing central axis, through the cup, and into his genitals, which would be tumescing in other circumstances. Hello, vibrating, er, toy. Waterhouse's genitals evidently know better than his brain does the danger he is in, because they are not, er, responding the way they would to such vibrations were these occurring, as Stephenson narrates, 'in other circumstances'.

Lawrence spends some time wandering aimlessly around the deck. Eventually he has to help open a hatch for some men, and then he realises that his hands are still clapped over his ears, and have been for a long time except for when he was wiping stuff out of his eyes. When he takes them off, the ringing has stopped, and he no longer hears airplanes. He was thinking that he wanted to go belowdecks, because the bad things are coming from the sky and we would like to get some big heavy permanent-seeming stuff between him and it, but a lot of sailors are taking the opposite view. He hears that they have been hit by one and maybe two of something that rhymes with "torpedoes," and that they are trying to raise steam. Officers and noncoms, black and red with smoke and blood, keep deputizing him for different, extremely urgent tasks that he doesn't quite understand, not least because he keeps putting his hands over his ears.

Probably half an hour goes by before he hits upon the idea of discarding his glockenspiel, which is, after all, just getting in the way. It was issued to him by the Navy with any number of stern warnings about the consequences of misusing it. Lawrence is conscientious about this kind of thing, dating back to when he was first given organ-playing privileges in West Point, Virginia. But at this point, for the first time in his life, as he stands there watching the Arizona burn and sink, he just says to himself: Well, to heck with it! He takes that glockenspiel out of its socket and has one last look at it, it is the last time in his life he will ever touch a glockenspiel. There is no point in saving it now anyway, he realizes; several of the bars have been bent. He flips it around and discovers that chunks of blackened, distorted metal have been impact-welded onto several of the bars. Really throwing caution to the winds now, he flings it overboard in the general direction of the Arizona, a military lyre of burnished steel that sings a thousand men to their resting places on the bottom of the harbor.

As it vanishes into a patch of burning oil, the second wave of attacking airplanes arrives. The Navy's antiaircraft guns finally open up and begin to rain shells down into the surrounding community and blow up occupied buildings. He can see human-shaped flames running around in the streets, pursued by people with blankets.

The rest of the day is spent, by Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse and the rest of the Navy, grappling with the fact that many two-dimensional structures on this and other ships, which were put into place to prevent various fluids from commingling (e.g. fuel and air) have holes in them, and not only that but a lot of shit is on fire too and things are more than a little smoky. Certain objects that are supposed to (a) remain horizontal and (b) support heavy things have ceased to do either.

Nevada's engineering section manages to raise steam in a couple of boilers and the captain tries to get the ship out of the harbor. As soon as she gets underway, she comes under concerted attack, mostly by dive bombers who are eager to sink her in the channel and block the harbor altogether. Eventually, the captain runs her aground rather than see that happen. Unfortunately, what Nevada has in common with most other vessels is that she is not really engineered to work from a stationary position, and consequently she is hit three more times by dive bombers. So it is a pretty exciting morning overall. As a member of the band who does not even have his instrument any more, Lawrence's duties are quite poorly defined, and he spends more time than he should watching the airplanes and the explosions. [pp. 77-80] Pearl Harbour, according to Lawrence Waterhouse. Although not all events are narrated strictly from Waterhouse's perspective, the whole affair has his stamp, his take, on it. For instance, Waterhouse spends the whole time 'wiping stuff out of his eyes', never realising, at least during the attack, that it is blood from a wound on his forehead. The comparison of the bomb falling through the deck of the Arizona to a character from a Warner Bros. cartoon is darkly hilarious, precisely because Waterhouse isn't making an ironic comparison - you can picture the simile popping into his head innocently, almost as if he were a child (although in other respects, of course, Waterhouse is 'all grown up'). A great deal of Waterhouse's time and energy is spent on the glockenspiel (which, admittedly, protects him from shrapnel, although he then has to deal with the hellish noise it produces), and at the very beginning, of course, he thinks the whole thing is a training exercise. The destruction wrought in the attack seems to have an air of unreality to it, when viewed from Waterhouse's perspective. He sees people running from buildings on fire, but it's almost as if he doesn't clue into the fact that they are, in fact, people; instead, he sees 'human-shaped flames running around in the streets'. The most vivid part of Stephenson's account of the attack on Pearl Harbour is, because it is from Waterhouse's perspective, the noise from the glockenspiel, warped and twisted as it is by the shockwave from the explosion of the Arizona, as well as the state of the instrument itself when Waterhouse goes to throw it overboard. It is telling that Waterhouse, at this point, doesn't think, 'fuck it' or 'to hell with it' upon deciding to throw the glockenspiel overboard; no, he thinks 'To heck with it!'. Waterhouse's reaction to all the noise, to clap his hands over his ears, is characteristic of children, if I am not mistaken. All this goes to show that Waterhouse has an eccentric way of looking at things. He retains a certain perceptive immaturity (let's call it) pretty much throughout the book, although his character development is toward greater savviness, wit (in the broadest sense), and even moral growth. This aspect of the style, then, is more prominent toward the beginning of the book, and recedes as Waterhouse grows in perceptiveness.

Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse walks down a street [in London] wearing the uniform of a commander in the United States Navy. ...That should provide enough material for a grasp of Stephenson's 'Waterhouse style'. It is generally discursive (in any sense of the word), humorous, and charmingly idiosyncratic. It is leavened with other stylistic and affective touches, of course, as are the other styles, but, as I say, in general, the 'Waterhouse style' can be characterised as I have done.

The curbs are sharp and perpendicular, not like the American smoothly molded sigmoid-cross-section curves. The transition between the sidewalk and the street is a crisp vertical. If you put a green lightbulb on Waterhouse's head and watched him from the side during the blackout, his trajectory would look just like a square wave traced out on the face of a single-beam oscilloscope: up, down, up, down. If he were doing this at home, the curbs would be evenly spaced, about twelve to the mile, because his home town is neatly laid out on a grid.

Here in London, the street pattern is irregular and so the transitions in ths square wave come at random-seeming times, sometimes very close together, sometimes very far apart.

A scientist watching the wave would probably despair of finding any pattern; it would look like a random circuit driven by noise, triggered perhaps by the arrival of cosmic rays from deep space, or the decay of radioactive isotopes.

But if he had depth and ingenuity, it would be a different matter.

Depth could be obtained by putting a green light bulb on the head of every person in London and then recording their tracings for a few nights. The result would be a thick pile of graph-paper tracings, each

one as seemingly random as the others. The thicker the pile, the greater the depth.

Ingenuity is a completely different matter. There is no systematic way to get it. One person could look at the pile of square wave tracings and see nothing but noise. Another might find a source of fascination there, an irrational feeling impossible to explain to anyone who did not share it. Some deep part of the mind, adept at noticing patters (or the existence of a pattern) would stir awake and frantically signal the dull quotidian parts of the brain to keep looking at the pile of graph paper. The signal is dim and not always heeded, but it would instruct the recipient to stand there for days if necessary, shuffling through the pile of graphs like an autist, spreading them out over a large floor, stacking them in piles according to some inscrutable system, pencilling numbers, and letters from dead alphabets, into the corners, cross-referencing them, finding patterns, cross-checking them against others.

One day this person would walk out of that room carrying a highly accurate street map of London, reconstructed from the information in all of those square wave plots.

Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse is one of those people. [pp. 143-6] Thank goodness those images were available; I don't know how the effect could have been produced without them. I should mention that similar digressions (by Lawrence Waterhouse or his grandson Randy) frequently include complex mathematics; this digression is probably the least difficult to follow. Lawrence Waterhouse is thinking about this while making his way to the London headquarters of Britain's cryptanalytical efforts - just barely paying attention to what is actually going on around him. Even when he thinks about matters of immediate attention (as when he thinks about Mary Smith, the desire of his heart and of, uh, other locations on his body), he tends to frame them in mathematical or cryptological terms (see, for example, pp. 677ff.; I couldn't quote it, but it is pretty much worth reading the whole book for). As often as not, he lets his brain get going in ruminating about things like what we have just seen, rather than focussing on the task at hand - in this case, crossing busy London streets.

I am going to briefly go over the 'Randy' and 'Bobby Shaftoe' styles. I shall do so in part due to considerations of space, and in part because I feel that, though effective, they aren't as distinctive as the 'Waterhouse' style (or, as we shall see, the 'Goto Dengo' style). This is not quite fair to Stephenson, who made Shaftoe and Randy more normal than Waterhouse. So, it would be fairer to say that with respect to their styles, the lack of the same degree of distinction is not a flaw, but characteristic, and characteristically good. I'll cite one passage for each of those two styles, and show in what ways the passages quoted are representative of their respective styles.

First, an example of the 'Randy style':

Randy wants to go down and look at the U-boat in person. Doug says evenly that Randy is welcome to do so, but he needs to draw up a valid dive plan first, and reminds him that the depth of the wreck is one hundred and fifty-four meters. Randy nods as if he had, of course, expected to draw up a dive plan.Moving on to the 'Shaftoe style':

He wants everything to be like driving cars, where you just hop in and go. He knows a couple of guys who fly planes, and he can still remember how he felt when he learned that you can't just get in a plane (even a small one) and take off—you have to have a flight plan, and it takes a whole briefcase full of books and tables and specialized calculators, and access to weather forecasts above and beyond the normal consumer-grade weather forecasts, to come up with even a bad, wrong [italics original] flight plan that will surely kill you. Once Randy had gotten used to the idea, he grudgingly admitted it made sense.

Now Doug Shaftoe's telling him he needs a plan just to strap some tanks on his back and swim a hundred and fifty-four meters (straight down, admittedly) and back. So Randy yanks a couple of diving books off the bungeed shelves of Glory IV and tries to come up with even a vague idea of what Doug's talking about. Randy has never gone scuba diving in his life, but he's seen them doing it on Jacques Cousteau and it seems straightfoward enough.

The first three books he consults contain more than enough detail to perfectly reproduce the crestfallenness that Randy experienced when he learned about flight plans [ditto]. Before he'd opened the books Randy had gotten out his mechanical pencil and his graph paper in preparation for making marks on the page; half an hour later he's still trying to get a handle on the contents of the tables, and he hasn't made any marks at all. He notes that the depths in these tables only go down as far as a hundred and thirty, and at that level they only talk in terms of staying down there five or ten minutes. And yet he knows that Amy, and the Shaftoe's colorful and ever-enlarging cast of polyethnic scuba divers, are spending much longer at this depth, and are in fact beginning to come up to the surface with artifacts from the wreck. ...

Randy begins to fear that the entire wreck is going to be stripped bare before he even makes any marks on his piece of graph paper. The divers show up, one or two each day, on speedboats or outrigger canoes from Palawan. ... They [ditto] all have diving plans. Why doesn't Randy have a diving plan?

He starts sketching one out based on the depth of one hundred and thirty, which seems reasonably close to one hundred and fifty-four. After working on it for about an hour (long enough to imagine all sorts of specious details) he happens to notice that the tale he's been using is in feet, not meters, [ditto] which means that all of these divers have been going down to a depth that is way more than three times as deep as the maximum that is even talked about on these tables.

Randy closes up all of the books and looks at them peevishly for a while. They are all nice new books with color photographs on the covers. He picked them off the shelf because (getting introspective here) he is a computer guy, and in the computer world any book printed more than two months ago is a campy nostalgia item. Investigating a little more, he finds that all three of these shiny new books have been personally autographed by the authors, with long personal inscriptions: two addressed to Doug, and one to Amy. The one to Amy has obviously been written by a man who is desperately in love with her. Reading it is like moisturizing with Tabasco.

He concludes that these are all consumer-grade diving books written for rum-drenched tourists, and furthermore that the publishers probably had teams of lawyers go over them one word at a time to make sure there would not be liability trouble. That the contents of these books, therefore, probably represent about one percent of everything that the authors actually know about diving, but that the lawyers have made sure that the authors don't even mention [ditto] that.

Okay, so divers have mastered a large body of occult knowledge. That explains their general resemblance to hackers, albeit physically fit hackers.

...

Randy does a sorting procedure on the diving books now: he ignores anything that has color photographs, or that appears to have been published within the last twenty years, or that has any quotes on the back cover containing the words stunning, superb, user-friendly, or, worst of all, easy-to-understand. He looks for old, thick books with worn-out bindings and block-lettered titles like dive manual. Anything with angry marginal notes written by Doug Shaftoe gets extra points.

...

Now all of a sudden he's reading stuff by guys whose names are preceded by naval ranks and succeeded by M.D.s and Ph.D.s and they are going on for dozens of pages about the physics of nitrogen bubble formation in the knee, for example. There are photographs of cats strapped down in benchtop pressure chambers. ... He comes to terms with the fact that the pressure at the depth of the wreck is going to be fifteen or sixteen atmospheres, meaning that as he ascends to the surface, any nitrogen bubbles that happen to be rattling around in his body are going to get fifteen or sixteen times as large as they were to begin with and that this is true whether those bubbles happen to be in his brain, his knee, the little blood vessels of the eyeball, or trapped beneath his fillings. He develops a sophisticated layman's understanding of dive medicine, which amounts to little because everyone's body is different—hence the need for each diver to have a completely different dive plan. Randy will need to figure out his body fat percentage before he can even begin marking up his sheet of graph paper.

It is also path-dependent. These divers' bodies get partially saturated with nitrogen every time they go down, and not all of it goes out of their bodies when they come back up—all of them, sitting around the Glory IV playing cards, drinking beer, talking to their girlfriends on their GSM phones, are all outgassing [ditto] all the time—nitrogen is seeping out of their bodies into the atmosphere, and each one of them knows more or less how much nitrogen's stuffed into his body at any given moment and understands, in a deep and nearly intuitive way, just exactly how that information propagates through any dive plan that he might be cooking up inside the powerful dive-planning supercomputer that each of these guys apparently carries around in his nitrogen-saturated brain.

One of the divers comes up with a plank from the crate that contained the stacks of gold sheets. It is in very bad shape, and it's still fizzing as gas comes out of it. Fizzing in a way that Randy has no trouble imagining his bones would do if he made any errors in working out his dive plan. ...

Glory IV has compressors for pumping air up to insanely high pressures to fill the scuba tanks. Randy develops an awareness that the pressure has to be insanely high or it won't even emerge from the tanks while these guys are down at depth. The divers are all being suffused with this pressurized gas; he half expects that one of these divers is going to bump into something and explode into a pink mushroom cloud.

...

"Randy?" says Doug Shaftoe, and beckons him into his wardroom.

...

"Check this out," Doug says, and pings one fingernail against a glass tray full of a transparent liquid. An envelope, unglued and spreadeagled, is floating in it. Randy bends over and peers at it. Something has been written on the back in pencil, but it's impossible to read because the flaps of the envelope have been spread apart. "May I?" he asks. Doug nods and hands him a couple of latex surgical gloves. "I don't have to file a diving plan for this, do I?" Randy asks, wiggling his fingers into the gloves.

Doug is not amused. "It's deeper than it looks," he says. [pp. 566-73] Now that I've chosen a passage and quoted it, dozens more come to mind that would have been funnier. Yet this passage is appropriate, because it is characteristic of Randy Waterhouse's experience in Cryptonomicon. He is beginning to grow as a character himself, but his development doesn't really take off until a bit later in the book, when he returns to his home in California to discover his house has been demolished by an earthquake (he is away from it, in the Philippines, to get away from his ex-girlfriend, with whom he has been negotiating the divestment of the property). That is another story, of course. The characteristics of the 'Randy style', for the most part, are these: 1) Lack of danger. Unlike Bobby Shaftoe or Goto Dengo, or even Lawrence Waterhouse (as we have seen), Randy rarely ventures into dangerous situations, at least not those that imperil life and limb. Indeed, his initial venture into the world of diving occurs in the library of the Glory IV as he tries to come up with a diving plan. This, for the most part, is how Randy spends his time; he does things that aren't very dangerous. It is a credit to Stephenson that Randy's 'adventures' are, if not exciting, then satisfying in such a way as to prevent boredom (Lawrence Waterhouse's adventures are much the same way, with, as we have seen, one or two exceptions). 2) Suffusion of irony: Actually, this may be said to be true of Cryptonomicon as a whole, but the ironic tone is especially prevalent in Randy's storyline, which is appropriate, given that it takes place in the late nineties during the rise of irony. The style for Lawrence Waterhouse rightly has a certain eccentric innocence; that for Shaftoe a brutal directness; and that for Goto Dengo a sense of tragic sadness - even though all of the styles are penetrated with an ironic tone, which is Stephenson's. 3) Introspectiveness: Randy spends a lot of time thinking about things, as this example shows. Notice, though, that his thinking tends to be more on the topic at hand. Where his grandfather spends his time in his own mental world while doing other things, Randy ruminates at length about what he is doing, when he is doing it. He needs to make a dive plan? Okay, it reminds him of when he learned about flight plans, and, hey, wait a minute, these books on diving aren't so useful after all, what can we learn here about the nature of the world of diving - and so on. 4) Other aspects: As Randy's comment to Doug at the end of the chapter indicates, he does have a certain clever wit to him; despite his professed social ineptness he is able to think of one-liners as 'I don't have to file a diving plan for this, do I?'. Randy also displays a certain self-deprecation, not immediately obvious in this passage, but even cursorily reading Cryptonomicon will demonstrate this aspect of the style. Stephenson does not, so far as I am able to tell, narrate the inner thoughts of the other major characters with such a self-deprecatory tone. Probably the best testament of Stephenson's literary skill, as I noted above, is how much fun he makes so dry a story as Randy's. If you omit all three of the World War II plotlines, the end product, consisting entirely of Randy's introspective plumbing, awkward romance of Amy, quiet travels from place to place (except at the end where there's some excitement), and so on, would still be an enjoyable read. And that says something about how well Stephenson writes, I think.

All of Shaftoe's men are down in the detachment's staging area [in Algeria]. This is a cave built into a sheer artificial cliff that rises from the Mediterranean, just above the docks. These caves go on for miles and there is a boulevard running over the top of them. But even the approaches to their particular cave have been covered with tents and tarps so that no one, not even Allied troops, can see what they are up to: namely, looking for any equipment with 2701 painted on it, painting over the last digit, and changing it to 2. The first operation is handled by men with green paint and the second by men with white or black paint.Last, but not least, is the 'Goto Dengo style'. As Goto Dengo's storyline is my favourite, I am going to spend a bit more time parsing his style than I did on the others (excepting the 'Waterhouse style', which, surprisingly, has occupied a considerable amount of space in this marginal commentary). Goto Dengo is introduced very early in the book, in Bobby Shaftoe's storyline, so that he won't be a stranger to us when we meet him again on his own terms later on.

Shaftoe picks one man from each color group [in order to do something else] so that the operation as a whole will not be disrupted. The sun is stunningly powerful here, but in that cavern, with a cool maritime breeze easing through, it's not really that bad. The sharp smell of petroleum distillates comes of all of those warm painted surfaces. To Bobby Shaftoe, it is a comforting smell, because you never paint stuff when you're in combat. But the smell also makes him a little tingly, because you frequently paint stuff just before [italics original] you go into combat.

Shaftoe is about to brief his three handpicked Marines on what is to come when the private with black paint on his hands, Daniels, looks past him and smirks. "What's the lieutenant looking for now do you suppose, Sarge?" he says.

Shaftoe and Privates Nathan (green paint) and Branph (white) look over to see that Ethridge has gotten sidetracked. He is going through the wastebaskets again.

"We have all noticed that Lieutenant Ethridge seems to think it is his mission in life to go through wastebaskets," Sergeant Shaftoe says in a low, authoritative voice. "He is an Annapolis graduate."

Ethridge straightens up and, in the most accusatory way possible, holds up a fistful of pierced and perforated oaktag. "Sergeant! Would you identify this material?"

"Sir! It is general issue military stencils, Sir!"

"Sergeant! How many letters are there in the alphabet?"

"Twenty-six, sir!" responds Shaftoe crisply.

Privates Daniels, Nathan, and Branph whistle coolly at each—other this Sergeant Shaftoe is sharp as a tack.

"Now, how many numerals?"

"Ten, sir!"

"And of the thirty-six letters and numerals, how many of them are represented by unused stencils in this wastebasket?"

"Thirty-five, sir! All except for the numeral 2, which is the only one we need to carry out your orders, sir!"

"Have you forgotten the second part of my order, Sergeant?"

"Sir, yes, sir!" No point in lying about it. Officers actually like it when you forget their orders because it reminds them of how much smarter they are than you. It makes them feel needed.

"The second part of my order was to take strict measures to leave behind no trace of the changeover!"

"Sir, yes, I do remember that now, sir!"

Lieutenant Ethridge, who was just a bit huffy first, has now calmed down quite a bit, which speaks well of him and is duly, silently noted by all of the men, who have known him for less than six hours. He is now speaking calmly and conversationally, like a friendly high school teacher. He is wearing the heavy-rimmed black military eyeglasses known in the trade as RPGs, or Rape Prevention Glasses. They are strapped to his head by a hunk of black elastic. They make him look like a mental retard. "If some enemy agent were to go through the contents of this wastebasket, as enemy agents have been known to do, what would he find?"

"Stencils, sir!"

"And if he were to count the numerals and letters, would he notice anything unusual?"

"Sir! All of them would be clean except for the number twos which would be missing or covered with paint, sir!"

Lieutenant Ethridge says nothing for a few minutes, allowing his message to sink in. In reality no one knows what the fuck he is talking about. The atmosphere becomes tinderlike until finally, Sergeant Shaftoe makes a desperate stab. He turns away from Ethridge and towards the men. "I want you Marines to get paint on all those goddamn stencils!" he barks.

The Marines charge the wastebaskets as if they were Nip pillboxes, and Lieutenant Ethridge seems mollified. Bobby Shaftoe, having scored massive points, leads Privates Daniels, Nathan, and Branph out into the street before Lieutenant Ethridge figures out that he was just guessing. They head for the meat locker up on the ridge, double-time.

These Marines are all lethal combat veterans or else they never would have gotten into a mess this bad—trapped on a gratuitously dangerous continent (Africa) surrounded by the enemy (United States Army troops). Still, when they get into that locker and take their first gander at PFC Hott, a hush comes over them.

Private Branph clasps his hands, rubbing them together surreptitiously. "Dear Lord—"

"Shut up, Private!" Shaftoe says, "I already did that."

"Okay, Sarge."

"Go find a meat saw!" Shaftoe says to Private Nathan.

The privates all gasp.

"For the fucking pig!" Shaftoe clarifies. Then he turns to Private Daniels, who is carrying a featureless bundle, and says, "Open it up!"

The bundle (which was issued by Ethridge to Shaftoe) turns out to contain a black wetsuit. Nothing GI; some kind of European model. Shaftoe unfolds it and examines its various parts while Privates Nathan and Branph dismember Frosty the Pig with vigorous strokes of an enormous bucksaw. [pp. 187-90] If you are struck by the oddness of what is going on, you should be. In many respects, despite the plainness of Bobby Shaftoe's thought processes (especially compared to those of Randy or Lawrence, or even Goto Dengo), his plotline has the most weirdest shit going on. 'Shit' is an appropriate term, too, for, as is blindingly obvious, profanity embedded into the narrative (and into dialogue) is characteristic of the 'Shaftoe style', moreso than in the other styles, although nearly all of them have some to a greater or lesser extent. The 'brutal directness' I referred to above is also stylistically evident, for Stephenson is licensed by the context to use what we would today call 'politically incorrect' or even 'wicked' terms; for instance, the description of Lieutenant Ethridge looking, due to his thick black glasses with the big elastic band, like a 'mental retard', or the naming of the same glasses as 'Rape Prevention Glasses'. The Shaftoe style is, of course, ironic (as I have pointed out repeatedly, irony is characteristic of Stephenson's style on the whole), but it is the kind of irony produced by the setting, rather than an irony inherent in the narrative; Shaftoe's ironic musings are prompted by what seems to be the madness of his superior officers and that of the orders they are giving him (e.g., painting over the unit's numeric designation in the first place, and then having to get all of the stencils covered in paint to prevent enemy agents from coming to conclusions about their activity - and if you think these are strange orders, you ain't seen nothin' yet), not to mention the madness of war generally. If Goto Dengo's storyline is the exploration of the tragic horror of war, Bobby Shaftoe's is the 'you laugh so you don't go batshit crazy' side. This passage, obviously, doesn't describe all of Bobby Shaftoe's violent adventures, or his reminiscences of the same, but Stephenson reveals a skill with handling 'action' sequences in his 'Shaftoe style', which is appropriate; all of the other major characters at one point or another engage in actions in which violence occurs, but the feel of those scenes differs from a Shaftoe action sequence; indeed, only in the 'Shaftoe style' can we really use the term 'action sequence' to describe the violent activity as adrenaline-pumping, rah-rah Hollywood stuff (although, mercifully, Stephenson doesn't play such action sequences straight, either, neither does he pretend that 'killing bad guys' is some kind of wonderful thing, even though we are plainly meant to side with Shaftoe). Shaftoe is prone to a certain amount of thoughtfulness, but, again, it is not the same kind of introspection that Randy or Lawrence undertake. Shaftoe's introspections tend to be pithy, laconic, and somewhat lacerating, as the comment on officers from his perspective demonstrates: 'No point in lying about it. Officers actually like it when you forget their orders because it reminds them of how much smarter they are than you. It makes them feel needed.' I think we have reached a point, in any case, where we have a good grasp of Stephenson's 'Shaftoe style'.

There are two passages which I would like to look at from Goto Dengo's storyline in order to analyse Stephenson's particular style for that character, so, let's turn to the first without further ado:

It's a hot cloudy day in the Bismarck Sea when Goto Dengo loses the war. The American bombers come in low and level. Goto Dengo happens to be abovedecks on a fresh-air-and-calisthenics drill. To breathe air that does not smell of shit and vomit maes him feel euphoric and invulnerable. ...That should suffice as an introduction to the 'Goto Dengo' style. This next passage should either confirm that Stephenson's use of similitudes in the first passage quoted is characteristic of the style - and so, you might say, characteristic of how Goto Dengo thinks - or whether that was simply a notable feature of that particular passage.

The emperor's soldiers are supposed to feel euphoric and invulnerable all the time, because their indomitable spirit makes them so. That Goto Dengo only feels that way while abovedecks, breathing clean air, makes him ashamed. The other soldiers never doubt, or at least never show it. He wonders where he went astray. Perhaps it was his time in Shanghai, where he was polluted with foreign ideas. ...

The troop transports are slow—there is no pretence that they are anything other than boxes of air. They have only the most pathetic armaments. The destroyers escorting them are sounding general quarters. Goto Dengo stands at the rail and watches the crews of the destroyers scrambling to their positions. Black smoke and blue light sputter from the barrels of their weapons, and much later he hears them opening fire.

The American bombers must be in some kind of distres. ... Whatever the reason, he knows they have not come here to attack the convoy because American bombers attack by flying overhead at a great altitude, raining down bombs. The bombs always miss because the Americans' bombsights are so poor and the crews so inept. No, the arrival of American planes here is just one of those bizarre accidents of war; the convoy has been shielded under heavy clouds since early yesterday.

The troops all around Goto Dengo are cheering. What good fortune that these lost Americans have blundered straight into the gunsights of their destroyer escort! And it is a good omen for the village of Kulu too, because half of the town's young men just happen to be abovedecks to enjoy the spectacle. They grew up together, went to school together, at the age of twenty took the military physical together, joined the army together, and trained together. Now they are on their way to New Guinea together. Together they were mustered up onto the deck of the transport only five minutes ago. Together they will enjoy the sight of the American planes softening into cartwheels of flame.

Goto Dengo, at twenty-six, is one of the old hands here—he came back from Shanghai to be a leader and an example to them—and he watches their faces, these faces he has known since he was a child, never happier than at this moment, glowing like cherry petals in the grey world of cloud, ocean, and painted steel.

Fresh delight ripples across their faces. He turns to look. One of the bombers has apparently decided to lighten its load by dropping a bomb straight into the ocean. The boys of Kulu break into a jeering chant. The American plane, having shed half a ton of useless explosives, peels sharply upward, self-neutered, good for nothing but target practice. The Kulu boys howl at its pilot in contempt. A Nipponese pilot would have crashed his plane into that destroyer at the very least!

Goto Dengo, for some reason, watches the bomb instead of the airplane. It does not tumble from the plane's belly but traces a smooth, flat parabola above the waves, like an aerial torpedo. He catches his breath for a moment, afraid that it will never drop into the ocean, that it will skim across the water until it hits the destroyer that stands directly across its path. But once again the fortunes of war smile upon the emperor's forces; the bomb loses its struggle with gravity and splashes into the water. Goto Dengo looks away.

Then he looks back again, chasing a phantom that haunts the edge of his vision. The wings of foam that were thrown up by the bomb are still collapsing into the water, but beyond them, a black mote is speeding away—perhaps it was a second bomb dropped by the same airplane. This time Goto Dengo watches it carefully. It seems to be rising rather than falling—a mirage, perhaps. No, no, he's wrong, it is losing altitude slowly now, and it plows into the water and throws up another pair of wings all right.

And then the bomb rises up out of the water again. Goto Dengo, a student of engineering, implores the laws of physics to take hold of this thing and make it fall and sink, which is what big dumb pieces of metal are supposed to do. Eventually it does fall again—but then it rises up again.

It is skipping across the water like the flat rocks that the boys of Kulu used to throw across the fish pond near the village. Goto Dengo watches it skip several more times, utterly fascinated. Once again, the fortunes of war have provided a bizarre spectacle, seemingly for no other reason than to entertain him. He savors it as if it were a cigarette discovered in the bottom of a pocket. Skip, skip, skip.

Right into the flank of one of the escorting destroyers. A gun turret flies straight up into the air, tumbling over and over. Just as it slows to its apogee, it is completely enveloped in a geyser of flame spurting out of the ship's engine room.

The Kulu boys are still chanting, refusing to accept the evidence of their own eyes. Something flashes in Goto Dengo's peripheral vision; he turns to watch another destroyer being snapped in half like a dry twig as its magazines detonate. Tiny black things are skip, skip, skipping all over the ocean now, like fleas across the rumpled bedsheets of a Shanghai whorehouse. The chant falters. Everyone watches silently.

The Americans have invented a totally new bombing tactic in the middle of a war and implemented it flawlessly. His mind staggers like a drunk in the aisle of a careening train. They saw that they were wrong, they admitted their mistake, they came up with a new idea. The new idea was accepted and embraced all the way up the chain of command. Now they are using it to kill their enemies.

No warrior with any concept of honor would have been so craven. So flexible. [italics original] ...

The American Marines in Shanghai weren't proper warriors either. Constantly changing their ways. Like Shaftoe. Shaftoe tried to fight Nipponese soldiers in the street and failed. Having failed, he decided to learn new tactics—from Goto Dengo. "The Americans are not warriors," everyone kept saying. "Businessmen perhaps. Not warriors."

Belowdecks, the soldiers are cheering and chanting. They have not the faintest idea what is really going on. For just a moment, Goto Dengo tears his eyes from the sea full of exploding and sinking destroyers. He gets a bearing on a locker full of life preservers.

The airplanes all seem to be gone now. He scans the convoy and finds no destroyers in working order.

"Put on the life jackets!" he shouts. None of the men seem to hear him and so he makes for the locker. "Hey! Put on the life jackets!" He pulls one out and holds it up, in case they can't hear him.

They can hear him just fine. They look at him as if what he is doing is more shocking than anything they've witnessed in the last five minutes. What possible use are life jackets?

"Just in case!" he shouts. "So we can fight for the emperor another day." He says this last part weakly.

One of the men, a boy who lived a few doors away from him when they were children, walks up to him, tears the life jacket out of his hands, and throws it into the ocean. He looks Goto up and down, contemptuously, then turns around and walks away.

Another man shouts and points: the second wave of planes is coming in. Goto Dengo goes to the rail to stand among his comrades, but they sidle away. The American planes charge in unopposed and veer away, leaving behind nothing but more skipping bombs.

Goto Dengo watches a bomb come directly toward him for a few bounces, until he can make out the message painted on its nose: bend over, tojo!

"This way!" he shouts. He turns his back to the bomb and walks back across the deck to the locker full of life preservers. This time a few of the men follow him. The ones who don't—perhaps five percent of the population of the village of Kulu—are catapulted into the ocean when the bomb explodes beneath their feet. The wooden deck buckles upwards. One of the Kulu boys falls with a four-foot long splinter driven straight up through his viscera. Goto Dengo and perhaps a dozen others make it to the locker on hands and knees and grab life preservers.

He would not be doing this if he had not already lost the war in his soul. A warrior would stand his ground and die. His men are only following him because he has told them to do it.

Two more bombs burst while they are getting the life preservers on and struggling to the rail. Most of the men below must be dead now. Goto Dengo nearly doesn't make it to the railing because it is rising sharply into the air; he ends up doing a chin-up on it and throwing one leg over the side, which is now nearly horizontal. The ship is rolling over! ...

He ... [is] standing on the summit of the ship now, a steel bulge that rises for no more than a man's height out of the water. ... Sea rushes in towards them. ... Then the Bismarck Sea converges on his feet from all directions at once and begins to climb up his legs. A moment later the steel plate, which has been pressing so solidly against the soles of his boots, drops away. ...

One of the men near him screams. He hears a noise approaching, like a sheet being torn in half to make bandages. Radiant heat strikes him in the face like a hot frying pan, just before Goto Dengo dives and kicks downwards. ...

He swims blind through an ocean of fuel oil. Then there is a change in the temperature and the viscosity streaming over his face... he must be in water now. ... Finally he risks opening his eyes. Ghostly, flickering light is illuminating his hands, making them glow a bright green; the sun must have come out. He rolls over on his back and looks straight up. Above him is a lake of rolling fire.

...

Now he need only pretend that the fire is a stone ceiling. He swims some more. But he did not breathe properly before diving, and he is close to panic now. He looks up again and sees that the water is burning only in patches.

He is quite deep, he realizes, and he can't swim well in trousers and boots. He fumbles at his bootlaces, but they are tied in double knots. He pulls a knife from his belt and slashes through the laces, kicks the boots off, sheds his pants and drawers too. Naked, he... brings his knees to his chest and hugs them. His body's natural buoyancy takes over. He knows that he must be rising toward the surface now, like a bubble. ...

His back feels cold. He explodes out of the fetal position and thrusts his head up into the air, gasping for breath. A patch of burning oil is almost close enough for him to touch, and the oil is trickling along the top of the ocean as if it were a solid surface. Nearly invisible blue flames seep from it, then turn yellow and boil off curling black smoke. He backstrokes away from a reaching tendril.

A glowing silver apparition passes over him, so close he can feel the warmth of its exhaust and read the English warning labels on its belly. The tips of its wing guns are sparkling, flinging out red streaks.

They are strafing the survivors. Some try to dive, but the oil in their uniforms pops them right back to the surface, legs flailing uselessly in the air. Goto Dengo first makes sure he is nowhere near any burning oil, then treads water, spinning slowly in the water like a radar dish, looking for planes. A P-38 comes in low, gunning for him. He sucks in a breath and dives. It is nice and quiet under the water, and the bullets striking its surface sound like the ticking of a big sewing machine. He sees a few rounds plunging into the water around him, leaving trails of bubbles as the water cavitates in their wake, slowing virtually to a stop in just a meter or two, then turning downwards and sinking like bombs. He swims after one of them and plucks it out of the water. It is still hot from its passage. He would keep it as a souvenir, but his pockets are gone with his clothes and he needs his hands. He stares at the bullet for a moment, greenish-silver in the underwater light, fresh from some factory in America.

How did this bullet come from America to my hand?

We have lost. The war is over.

I must go home and tell everyone.

...

He lets the bullet go again, watches it drop towards the bottom of the sea where the ships, and all of the young men of Kulu, are bound. [pp. 396-404] A few notes before we look at some stylistic points. First, I couldn't find any evidence of a Japanese village called 'Kulu', so I imagine that Stephenson made it up (it isn't the only made-up location in the book). I cannot, therefore, provide any more detail about it. Second, for you World War II buffs, here is a picture of the P-38 Lightning, a workhorse of the Pacific War, and here is what Wikipedia has to say about it. Incidentally, one of the shining moments of the P-38 was in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, which resulted in the destruction of a Japanese convoy sent to reinforce New Guinea. My guess is that is this battle in which Stephenson places the doomed convoy carrying Goto Dengo and the boys from Kulu. You can find a number of historic newsreels about the battle on YouTube. Two of note are respectively 3 minutes and 9 minutes long. (I also found similar footage in a dreadful video featuring a racist jazz number from the war and a great deal of vicious posturing about why its okay to do really nasty things to the enemy because he's done them to you, evidently having more to do with the war on terror than the war with Japan). The bombs behaving like skipping rocks are the result of a type of bombing called 'skip bombing', which was, indeed, employed during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, to great effect, as Stephenson so vividly demonstrates. None of the videos I found on the battle demonstrated this kind of bombing very well, but seeing as they were made in medias res, perhaps that is asking too much of the cameramen! Meanwhile, the final words of the chapter, about the ships carrying the young men of Kulu to the bottom of the sea (not to mention the slaughter of the entire convoy which preceded it) reminds me of the Great Big Sea rendition of 'Recruiting Sergeant' (frequently spelled incorrectly as 'sargeant', as it happens). It doesn't take much imagination to hear the lyrics and refer them to the boys of Kulu, who, as that elegaic passage notes, 'grew up together'. They would die together. Anyway, on to stylistic matters. On re-reading this passage, the first thing I noticed was the preponderance of similes. Many of the things that happen are 'like' something else: the faces of the young men of Kulu are 'glowing like cherry petals'; the first bomb Goto Dengo sees jets across the water in a parabolic course 'like an aerial torpedo'; the bullets striking the surface of the water sound 'like the ticking of a big sewing machine'; the heat of the fire strikes Goto Dengo 'like a hot frying pan'; and so on. This is very obviously distinct, but is it characteristic of the 'Goto Dengo' style? I am not so sure, now I think of it. Like the 'Shaftoe' style, I find that the 'Goto Dengo' style is terse, but it is much more sad in tone, much less darkly humorous, than the former style is. Goto Dengo sees a lot of people die, for instance, but Stephenson never writes of them the way he does of those whom Shaftoe witnesses dead (such as Gerald Hott, the unfortunate butcher in the example of the 'Shaftoe' style quoted above). The tone of the 'Goto Dengo' style is much more elegaic generally. That this is so will be more than adequately demonstrated by my other citations on this style from Cryptonomicon. Although, as we have seen, Goto Dengo is atypical for a Japanese warrior of the Second World War, he still sees the world from that perspective, and so it is characteristic of the 'Goto Dengo' style, at least until part way through his development, when he becomes both cynical yet determined. I should say that what is characteristic of the 'Goto Dengo' style in this respect, in the early stages of the book, is the shock that Goto Dengo has when he tries to fit the world he experiences into the mindset in which he has been trained - unsuccessfully, as it turns out - to dwell. Examples of this are his mistaken impression of how the American bombing run will fare, and his incredulity at the skipping bombs; the lesson has sunk in (if I may indulge in dark humour) when he grasps the American bullet in his hand after the convoy has been destroyed. Even so, as we shall see, Goto Dengo is slow to abandon the warrior mindset, even after it has been overthrown by other shocks, and even when he is able to set it aside from time to time.

Goto Dengo survives the destruction of his convoy, and through a series of what can only be called misadventures, winds up recuperating in the Philippines, then under Japanese control. But the place where he is being hospitalised is not a military hospital, which is where you'd think he'd end up:

Goto Dengo lies on a cot of woven rushes for six weeks, under a white cone of mosquito netting that sitrs in the breezes from the windows. ... Outside the windo, an immense stairway has been hand-caved up the side of a green mountain. When the sun shines, the new rice on those terraces fluoresces; green light boils into the room like flames. ... The wall of his room is plain, cream-colored plaster spanned with forking deltas of cracks, like the blood vessels on the surface of an eyeball. It is decorated only with a crucifix carved out of napa wood in maniacal detail. Jesus's eyes are smooth orbs without pupil or iris, as in Roman statues. He hangs askew on the crucifix, arms stretched out, the ligaments probably pulled loose from their moorings now, the crooked legs, broken by the butt of a Roman spear, unable to support the body. A pitted, rusty iron nail transfixes each palm, and a third suffices for both feet. Goto Dengo notices after a while that the sculptor has arranged the three nails in a perfect equilateral triangle. He and Jesus spend many hours and days staring at each other through the white veil that hangs around the bed; when it shifts in the mountain breezes, Jesus seems to writhe. An open scroll is fixed to the top of the crucifix; it says I.N.R.I. Goto Dengo spends a long time trying to fathom this. I Need Rapid something? Initiate Nail Removal Immediately?This ends my exploration of the distinctive styles of Cryptonomicon. I think I have thoroughly (if not more than thoroughly) demonstrated that Stephenson displays the ability to write distinctive styles for each of his major characters, even though there are many stylistic notes that pervade the work as a whole. This is an excellence on its own terms, and is made even better by the fact that Stephenson is a writer of no mean skill. I wholeheartedly recommend Cryptonomicon to anyone. At worst, you might say it is 'better-than-average summer reading'; but I would say that it is one of the better books I have read for The Marginal Virtues. (It goes almost without saying that I would rate it more highly than as 'summer reading' of any kind.) I enjoyed the book and had a good time both reading it, and re-reading it (in bits and pieces) for this marginal commentary, which says something about its quality, in my view. A lot more could be said about Cryptonomicon, and probably has been, but at this point, I bring my marginal commentary to an end.

The veil parts and a perfect young woman in a severe black-and-white habit is standing in the gap... carrying a bowl of steaming water. She peels back his hospital gown and begins to sponge him off. Goto Dengo motions towards the crucifix and asks about it—perhaps the woman has learned a little Nipponese. If she hears him, she gives no sign. She is probably deaf or crazy or both; the Christians are notorious for the way they dote on defective persons. ... Goto Dengo's mind is still playing tricks with him, and looking down at his naked torso he gets all turned around for a moment and thinks that he is looking at the nailed wreck of Jesus. His ribs are sticking out and his skin is a cluttered map of sores and scars. He cannot possibly be good for anything now; why are they not sending him back to Nippon? Why haven't they simply killed him? ...

He drifts away into a fever, and sees himself from the vantage point of a mosquito trying to find a way in through the netting: a haggard, wracked body splayed, like a slapped insect, on a wooden trestle. The only way you can tell he's Nipponese is by the strip of white cloth tied around his forehead, but instead of an orange sun painted on it it is an inscription: I.N.R.I.

A man in a long black robe is sitting beside him, holding a string of red coral beads in his hand, a tiny crucifix dangling from that. ... "Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum," he is saying. "It is Latin. Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews."

"Jews? I thought Jesus was Christian," said Goto Dengo.

The man in the black robe just stares at him. Goto Dengo tries again: "I didn't know Jews spoke Latin."

One day a wheeled chair is pushed into his room; he stares at it with dull curiosity. He has heard of these things—they are used behind high walls to transport shamefully imperfect persons from one room to another. Suddenly these tiny girls have picked him up and dropped him into it! One of them says something about fresh air and the next thing he knows he's being wheeled out the door and into a corridor! They have buckled him in so he doesn't fall out, and he twists uneasily in the chair, trying to hide his face. The girl rolls him out to a huge verandah that looks out over the mountains. ... On the wall behind him is a large painting of I.N.R.I. chained naked to a post, shedding blood from hundreds of parallel whip-marks. A centurion stands above him with a scourge. His eyes look strangely Nipponese.

Three other Nipponese men are sitting on the verandah. One of them talks to himself unintelligibly and keeps picking at a sore on his arm that bleeds continuously into a towel on his lap. Another one has had his arms and face burned off, and peers out at the world through a single hole in a blank mask of scar tissue. The third has been tied into his chair with many wide strips of cloth because he flops around all the time like a beached fish and makes unintelligible moaning noises.

Goto Dengo eyes the railing of the verandah, wondering if he can muster the effort to wheel himself over there and fling his body over the edge. Why has he not been allowed to die honorably?

...

Black-robe laughs out loud at Goto Dengo during his next visit. "I am not trying to convert you," he says. "Please do not tell your superiors about your suspicions. We have been strictly forbidden to proselytize, and there would be brutal repercussions."

"You aren't try to convert me with words," Goto Dengo admits, "but just by having me here." His English does not quite suffice.

Black-robe's name is Father Ferdinand. He is a Jesuit or something, with enough English to run rings around Goto Dengo. "In what way does merely having you in this place constitute proselytization?" Then, just to break Goto Dengo's legs out from under him, he says the same thing in half-decent Nipponese.

"I don't know. The art."

"If you don't like our art, close your eyes and think of the emperor."

"I can't keep my eyes closed all the time."

Father Ferdinand laughs snidely. "Really? Most of your countrymen seem to have no difficulty with keeping their eyes tightly shut from cradle to grave."

"Why don't you have happy art? Is this a hospital or a morgue?"

"La Payson is important here," says Father Ferdinand.

"La Payson?"

"Christ's suffering. It speaks deeply to the people of the Philippines. Especially now."

Goto Dengo has another complaint that he is not able to voice until he borrows Father Ferdinand's Japanese-English dictionary and spends some time working with it.

"Let me see if I understand you," Father Ferdinand says. "You believe that when we treat you with mercy and dignity, we are implicitly trying to convert you to Roman Catholicism."

"You bent my words again," says Goto Dengo.

"You spoke crooked words and I straightened them," snaps Father Ferdinand.

"You are trying to make me into—one of you."

"One of us? What do you mean by that?"

"A low person."

"Why would we want to do that?"

"Because you have a low-person religion. A loser religion. If you make me into a low person, it will make me want to follow that religion."

"And by treating you decently we are trying to make you into a low person?"

"In Nippon, a sick person would not be treated as well."

"You needn't explain that to us," Father Ferdinand says. "You are in the middle of a country full of women who have been raped by Nipponese soldiers.

Time to change the subject. ...

"I will get better," Goto Dengo says. "No one will know that I was sick."

"Except for us. Oh, I understand. You mean, no Nipponese people will know. That's true."

"But the others here will not get better."